[From The Denver Business Journal; more information including a 3:09 minute video is available here]

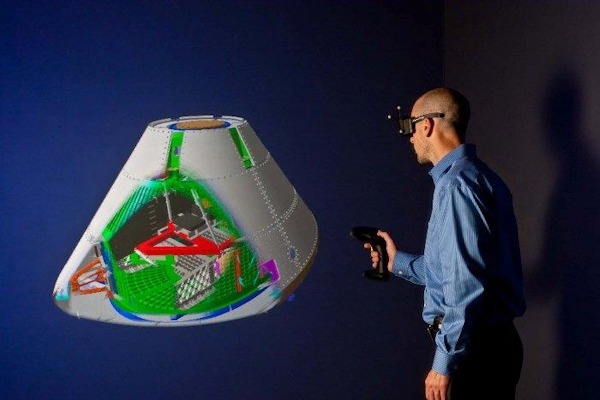

[Image: A demonstration of what an engineer sees inside Lockheed Martin’s Collaborative Human Immersive Laboratory]

Inside Lockheed Martin’s out-of-this-world virtual-reality lab

Denver Business Journal – by Greg Avery

Date: Monday, January 24, 2011 – Last Modified: Tuesday, January 25, 2011

The newest advance at Colorado’s Lockheed Martin Space Systems Co. campus isn’t as out-of-this-world as some of what’s made there, but it’s not exactly of this world, either.

The Littleton-based division of Lockheed Martin Corp., the Bethesda, Md.-based defense and aerospace giant, this week publicly unveiled a virtual reality lab where its engineers can test and improve satellite and space vehicle designs before they physically exist.

In the company’s Collaborative Human Immersive Laboratory, teams of engineers can virtually walk around their creation, look at it from every angle, virtually add parts to it and interact with it as if it were in the room. But it’s not.

“We wanted this so that when you come in the door, you work different than you have ever worked before,” said Jeff Smith, director of special projects who oversaw the CHIL’s development for Lockheed Martin Space Systems Co. “We think we’ve done it.”

The CHIL fills part of a large building where parts of Titan and, as recently as last year, Atlas rockets used to be assembled on Lockheed Martin’s campus near the mouth of Waterton Canyon in the Jefferson County foothills southwest of Denver.

The lab has the air of a tidy Hollywood special effects studio. Inside the CHIL, 24 cameras, almost theatrical lighting, motion censors and clusters of flat-screen monitors break up the otherwise uniform blackness of the walls.

In one part of the lab is “The Cave,” a small stage-like area that can be completely closed in by large screens.

I put on special 3-D glasses and stepped into The Cave to see a slightly ghostly mock-up of a satellite’s frame hanging in the air in front of me.

No one in the CHIL would mistake what they were seeing for the real world — objects look like CAD designs and people’s virtual avatars like very plain versions of what’s seen in the Second Life virtual reality game.

But my legs wanted to step up on to the animated-looking steps at the bottom of my peripheral vision.

The 3-D glasses communicate with sensors around The Cave and adjust the detailed image so that it moved in relation to my perspective. I could walk around its sides, bend down and look it from below or lean forward for a closer look at the detail of a faster or a bolt. When I did, my hand instinctively reached out to touch it.

This is the immersive experience Smith and his team is after.

Outside The Cave is a larger, open floor space surrounded by cameras where up to four people can put on virtual reality goggles, strap sensors on their body and do things like virtually assemble pieces of a project.

Rooms adjoining the CHIL feature a small cluster of work cubicles and an up-to-date conference room, all of which can tie directly into the 3-D virtual reality taking shape inside the lab.

The idea is to have teams of engineers and others working on projects nearby on their computers, making design adjustments and adding to the collaboration unfolding in the lab’s virtual spaces.

The CHIL is meant to be more than gee-whiz cutting edge. It’s hoped to save Lockheed Martin money.

By testing out designs and virtually interacting with a project — a satellite, space probe or the marquee Orion capsule being developed for NASA — flaws in thinking can be spotted or improvements invented without having to make a real-world prototype.

With cheaper virtual testing, engineers can be freed to innovate, more quickly discover what ideas are dead ends, assess designs for safety and figure out how configure things for more efficient assembly, Smith said.

“Our motto has been ‘moving electrons is easier than moving molecules’,” he said. “If you do this right, you can reduce time and expense.”

Smith said his small CHIL team late last year had an experienced engineer test out the system. The engineer had helped build projects that are now in space, and his conclusion was that the technology would’ve completely changed how they approached design and assembly of projects, Smith said.

Lockheed Martin has a couple other labs like CHIL elsewhere. Its aeronautics division built a similar lab in Fort Worth, Texa,s to help in the development of Joint Strike Fighter airplane for the Air Force.

The space systems division built the CHIL primarily to help speed development of the next generation of global positioning satellites it’s building for the U.S. Air Force. The $1.4 billion GPS III first phase will add 100 new jobs locally and another 400 at Lockheed Martin Space Systems campus outside Philadelphia.

The local campus is where the satellites’ design and assembly with be tested, and the building that’s home to CHIL is being expanded to accommodate the work.

CHIL’s virtual reality technology is already helping, Smith said. Using a contractor’s 3-D mock-up of the new space, the company tested the placement and design of different work areas and found that, by rearranging, them they could reduce the number of times satellites had to be lifted or moved during testing.

(That’s a potentially critical improvement — Lockheed Martin once took a $30 million charge after, in 2003, it dropped a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration satellite it was building.)

Smith didn’t say how much CHIL cost to make.

The design, construction and software integration to more than six months. The banks of video processors, the computer servers, sensors, cameras, lights, monitors and specialized virtual reality glasses certainly aren’t cheap.

But the lab — which will require only one employee to operate day-to-day — aims to pay for itself with design efficiencies and leaps in innovation.

“We wanted to make sure we can prove out the business case before we go and do others,” Smith said.