[A Texas startup has developed a new potential solution to the problems of motion sickness while using presence-evoking technologies, as recounted in this story from VentureBeat (where the original includes more images). For related coverage see VentureBeat’s “How and why our experiments with virtual reality motion made us ill,” and an Adweek story about companies’ demonstrations of the effect of even small lags in VR to promote 5G wireless technology. –Matthew]

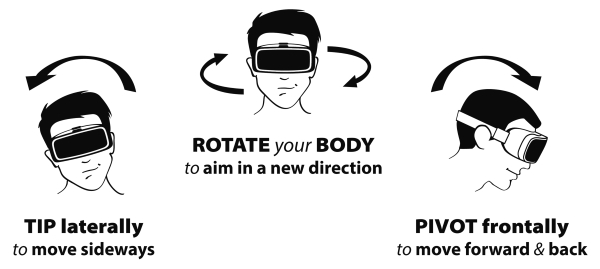

[Image: How BodyNav works. Credit: MonkeyMedia]

MonkeyMedia’s BodyNav lets you navigate VR without getting sick

Dean Takahashi

February 6, 2018

Motion sickness is one of the challenges holding back virtual reality from reaching larger audiences. And MonkeyMedia, a small tech firm in Austin, Texas, believes it has solved the problem with BodyNav, a way to navigate VR in a natural way.

BodyNav doesn’t rely on using a handheld game controller or hand controls for movement. MonkeyMedia Eric Bear said in an interview with GamesBeat that poor synchronization and interfaces between such controls and what your eyes see can make any person sick.

So Bear and Rachel Strickland, frequent co-inventor and media artist, dreamed up a system where you can navigate using body movements, such as physically leaning your head forward to move forward, inside a 3D virtual landscape. You can use similar motions to move in different directions. This system allows your body to move in sync with the direction you are moving. And that reduces any problem related to motion sickness, Bear said.

It’s an interesting invention that comes from a small team that has been doing research and development for 25 years. Bear said the company has received seven patents on the invention, and it has a couple of more patent applications pending.

“We didn’t set out to solve this problem, but we found a new way of doing navigation,” Bear said.

Bear said that sensors which are already in VR headsets — accelerometers and gyroscopes — can detect the head movement. In fact, some games such as Oculus’ Dead & Buried, a Western gunslinger game, use those sensors to detect whether you are ducking behind cover in a VR gun battle. It also has applications in augmented reality and first-person video drone piloting.

By using your head to move around in VR, that means you can stopping using your fingers to do that work with game controllers. In a shooting game, that simplifies the “cognitive overload” of a game controller that mystifies all but the most dedicated hardcore gamers, Bear said.

“If you change your view and movement with your hands and still have to pull a trigger, that represents a lot of cognitive load,” Bear said. “We take the movement stuff out. Now you can sneak around corners and move fast by leaning. If it’s too complex for you to learn a controller, that’s not your failure. It’s a failure of the game designer for creating too heavy a cognitive load. It’s for us to figure out how we screwed up in designing user interfaces for people.”

If you no longer have to move your virtual body with a left thumb stick, then you only have to use your hands to worry about tasks such as aiming a gun (which can be pointed in a different direction from the one where you are moving) or pulling a trigger. That simplifies the control tasks, enables more people to learn how to navigate in VR, and reduces the motion sickness at the same time. (Of course, it will force the expert first-person shooter players to get used to a new form of navigation).

Bear said that BodyNav will be available for licensing to game developers, who can use an applications programming interface to integrate it into their VR games and other apps.

BodyNav is consistent with Bear’s belief that interfaces and virtual interactions should be “human centered,” rather than gadget centered.

Rob Bamforth, analyst at research firm Quocirca, said in a statement, “Making the physical experience align with human expectations, as I experienced with MonkeyMedia’s BodyNav technology, is critical not only for an effective VR experience, but also for avoiding digitally induced motion sickness.”

Besides VR users, motion sickness has long bothered drone pilots and some players of 2D games as well. Traditional stereoscopic headset interfaces use multiple sensor axes (for instance, rotate left/right, pivot up/down, tip left/right) to establish viewer orientation, while requiring handheld controllers (joysticks, gamepads, keyboards, etc.) for locomotion.

Visually “moving” through space while in a sedentary posture creates sensory imbalances that can cause dizziness and nausea in the viewer, Bear said. BodyNav technology creates more intuitive virtual interactions by remapping control axes to accomplish both orientation and locomotion with natural body movement. This provides the organic equilibrium needed to circumvent sensory imbalances, he said.

Richard Garriott de Cayeux, the legendary video game pioneer (creator of the Ultima series) and private astronaut, tried out BodyNav.

“Fundamentally, MonkeyMedia has solved a really important problem within the VR community,” said Garriott de Cayeux, in a statement. He added, BodyNav “doesn’t require a joystick and you don’t get motion sickness. It has a very natural feel and seems to solve vestibular dysfunction. An outstanding solution.”

BodyNav doesn’t use custom hardware. It uses distinct sensor axes for independent functions to maintain equilibrium in the body’s proprioceptive system. Viewers simply lean, using either their head or torso, to move themselves through virtual spaces, or to move their drones through remote physical spaces. This allows the sensory receptors, which receive stimuli internally and relate to the body’s position and movement, to properly engage with virtual or remote content, synchronizing visual and vestibular (inner ear) senses and reducing motion sickness-inducing factors.

“When you get motion sickness, the inner ear fluids are out of sync with your eyes,” Bear said. “You have movement in your visual field, but no expected movement in your body through your inner ear, and that tells your stomach that things are screwed up, and you get sick,” Bear said.

This idea of using body movements for navigation has been a long time coming, but it basically gets us much closer to moving more naturally, as we do in real life, in the virtual world. Bear and his wife Janna worked on the first wave of VR in the early 1990s, and once again in a brief revival in the late 1990s.

He set it aside as VR failed, and made money inventing some other things (such as tech related to DVDs and Blu-ray discs) in the meantime that allowed him and his wife to continue their fundamental research. Overall, the Bears have more than 100 patents.

Bear said he was working with videographer Strickland on some museum-related visuals. In 2012, they built an iPad app that allowed you to use the tablet as a window into a virtual world. That was done before. But they needed a navigation system where you could move through the world without using your hands (because your hands were busy holding the tablet).

“We didn’t want to muck up the user interface,” Bear said.

That led them to use the motion sensor in the tablet to detect your body movements and to translate those into motion. You can move sideways in a game world, or strafe, by leaning sideways physically.

That experiment led to the creative spark for using the navigation in other applications.

“It felt similar to riding a Segway, which is phenomenal,” Bear said. “As soon as I used the accelerometer and motion controls in VR to control the movement, the motion sickness was gone.”

The patents cover inventions known as BodyNav, Walk-in Theater, and Teleport. Walk-in Theater covers the use of your body to engage with videos, and Teleport is for piloting drones.

BodyNav, Walk-in Theater and Teleport are covered by the following U.S. patent numbers: 9,563,202; 9,579,586; 9,612,627; 9,656,168; 9,658,617; 9,782,684; 9,791,897; and 15/694,210. MonkeyMedia is self-funded.